If you’re anything like me, the stupidity and immorality of modern society has tempted you to retreat to a cabin 100 miles from nowhere. Maybe you’ve thought through this scenario: You’d take your spouse and dog, a few solar panels, you’d get a small walk-behind tractor, a food dehydrator, a couple of rifles, and you’d drop out. As things worsen you’d have your land, your cabin, your food, and a .308 to politely dissuade anyone from taking it from you.

If that feeling resonates, it’s probably because there are already plenty of good reasons to despise society, and more seem to arrive daily:

- Some asshole in Brazil is actually encouraging rapid destruction of the Amazon, possibly past the point that triggers a total collapse;

- A new report shows that millions of species are being threatened by climate change, yet it’s not taken seriously by policymakers;

- Your neighbor across the street spends ten minutes warming up or cooling their SUV before driving the half mile to the grocery store to pick up steaks;

- Legions of consumers still buy carbon-intensive status symbols to differentiate themselves from others; and

- Lots of people make poor financial decisions, leaving us woefully unprepared for the clime ahead.

The parable of the ant and the grasshopper illustrates some of these points. In this tale the grasshopper spends the summer gallivanting while the ant diligently prepares for winter. When winter arrives, the grasshopper begs the ant for food. I’m not sure how the story ends, but in a few versions the ant turns its back on the grasshopper, which makes sense as the ant should be pissed at the grasshopper. The story does a fine job illustrating the value of industriousness and preparation, but as a practical matter, the grasshopper is hungry and likely poses a problem for the well-supplied ant. The ant could join forces with other ants to fend off the hungry grasshopper, or it might lend him a bit of food and try to convert him to more productive and prudent ways? In no scenario does the ant ward off the grasshopper or any of its hungry grasshopper friends all by itself.

Community matters. You can harden yourself as a target, but ultimately unconverted swarms of grasshoppers will overwhelm you if you aren’t part of a small army of other ants. Bill McKibben, a Middlebury College professor and esteemed environmental thinker and advocate, and founder of 350.org, is certainly not the image of the rugged, military-trained, survivalist from whom you’d expect to read:

“If you think about the cramped future long enough, for instance, you can end up convinced that you’ll be standing guard over your vegetable path with your shotgun, warding off the marauding gang that’s after your carrots. The marines aren’t going to be much help there—they’re not geared for Mad Max—but your neighbors might be.”

– Bill McKibben, Eaarth, pp. 145-146

McKibben’s thinking, not surprisingly, is also supported by actual military-trained strategists with whom I’ve spoken. Even the most elite special forces operator can’t defend a large swath of land by themselves.

Communities also fare better against natural adversaries when people work together and neighbors trust and rely on one another. Daniel Aldrich, Director of the Security and Resilience Studies Program at Northwestern University, studied over 100 towns impacted by the 2011 Tsunami in Japan. After normalizing for a number of confounding variables, he and his colleagues found that communities with higher levels of social cohesion suffered fewer Tsunami-related casualties. Aldrich mentioned ties between town residents as being the key that enabled communities to shepherd their members out of harm’s way, and the community’s ties to the greater society and government as being the main supports for recovery after the devastation. His suggestions for building social resilience include getting to know your neighbors, supporting community events, and increasing volunteerism. This is truly a hard pill to swallow for the die-hard misanthrope, but the clime ahead will necessitate all sorts of difficult maneuvers that get us out of our comfort zones, maneuvers that put you in positions where you may need to interact and coordinate with your fuel wasting, SUV-driving neighbors. It’s sour, but we have to bite into the lemon and engage. After twenty years of watching clips from late night political comedy and thinking I’m in on the joke—that I’m some know-better, third-party observer of a never-ending circus—I realize that the cynicism it’s bred in me isn’t helpful. We’re not third-party observers, some of us are just poorly-engaged citizens coming around to the realization that engagement with our local bicycle co-ops or HOAs might be as valuable as time spent stacking freeze-dried food and lobbing rounds down range.

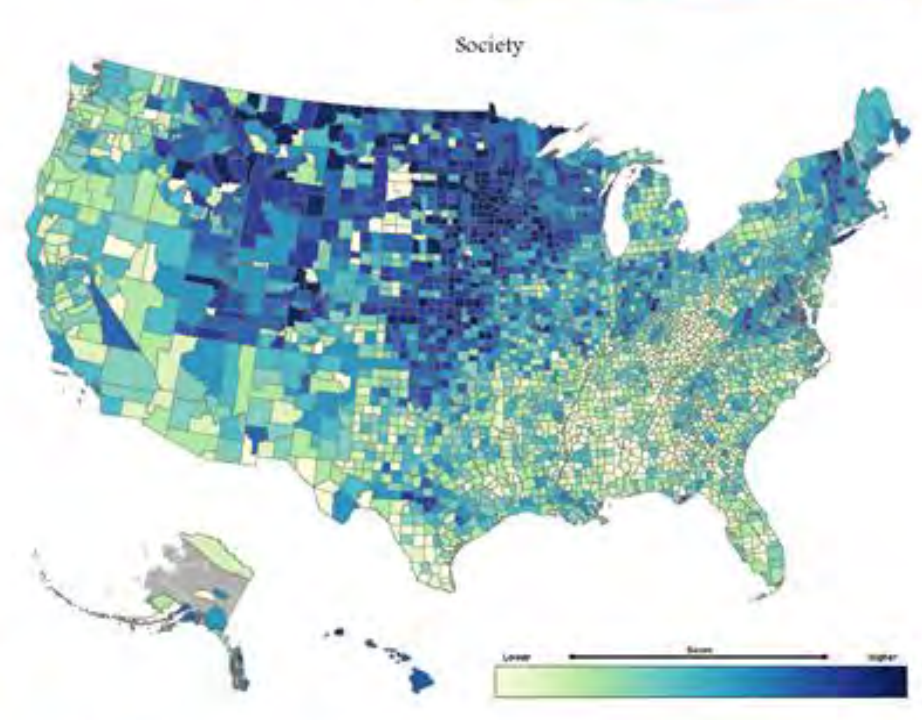

Lest we digress further, from a practical standpoint it probably doesn’t make sense to invest efforts in building community in areas where there’s really low social cohesion, and it’s equally ill-advised to move to areas where strong social cohesion will be tested by nearly insurmountable climate challenges. Obviously, the best bet would be to target areas with both strong social cohesion and lower climate risk. As luck would have it, in 2017 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released a Climate Resilience Screening Index (CRSI) that evaluates every county in the U.S. based on numerous metrics feeding into five main risk domains: Risk, Governance, Built Environment, Natural Environment, and Society. These five risk domains are weighted and used to arrive at a single index score for each county or parish, called the CRSI score. The assessment is worthy of review, but it’s important to remember that, with the sole exception of sea level rise, it reflects risks as they are today, not what they’re expected to be decades from now under likely climate change scenarios. Changes in risks could then have a cascading impact on other risk domains (E.g., Kauai, Hawaii, has a very high Society score, but will people and institutions remain if the county runs out of fresh water?). Still, the Society scores offer a good assessment of the relative strength of favorable demographics, economic diversity, health characteristics, labor and trade services, safety and security, social cohesion, social services, and socio-economics.

In summary: Hermits will fail to clime ahead. Social cohesion and other society factors are critical; you should only consider investments in, or relocation to, areas with high society scores, and then be prepared to invest in sustaining these communities. While areas change, it’s reasonably foreseeable that strong communities in low climate-risk areas will continue being strong communities. Also, they’re generally just nice places to live.

I’m certain that the final CRSI metrix scores reflected in Table E-2 of the EPA report, which shows the lowest sustainability/resilience scores throughout the Southeast and Midwest of the U.S., which corresponds with historical control of those areas by Republicans, can’t be a coincidence…or can it? An interesting study which raises significant questions about where our country is going in the days ahead.